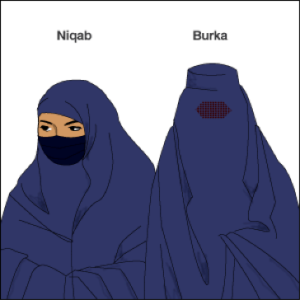

As reported by the Ottawa Citizen, a trial judge, applying a Canadian Supreme Court ruling, ordered a devout Muslim woman to testify in court without her niqab.[1] She is testifying against men she accuses of sexual abuse while she was a minor. Her religion dictates that she wears her niqab when facing men who are not relatives. Below is a graphic from the BBC illustrating two types of Muslim face coverings.[2]

This trial clearly pits the right to confront witnesses and the right to a fair trial against the free exercise of religion. In Canada, the Supreme Court determined that this issue must be addressed on a case-by-case basis:

“A clear rule that would always, or one that would never, permit a witness to wear the niqab while testifying cannot be sustained. Always permitting a witness to wear the niqab would offer no protection for the accused’s fair trial interest and the state’s interest in maintaining public confidence in the administration of justice. However, never permitting a witness to testify wearing a niqab would not comport with the fundamental premise underlying the Charter that rights should be limited only to the extent that the limits are shown to be justifiable. The need to accommodate and balance sincerely held religious beliefs against other interests is deeply entrenched in Canadian law.”[3]

Essentially, the Canadian Supreme Court set out a four-prong test for lower court judges to use when determining if the niqab interferes with the trial. As summarized by the CBC, the prongs are:

- Does she have a sincere belief in her religion?

- Does wearing a veil create a serious risk to trial fairness?

- Is there any other way to accommodate her?

- If no, does what the court called the “salutary” effects of ordering her to remove her niqab outweigh the “deleterious” effects of doing that?[4]

The trial judge applied the test in the remanded case and found in favor of the rights of the accused. Normally, in Canada or the U.S. this would be the end of the issue and either N.S. would testify without her niqab or the trial would not move forward. But her lawyer is trying another tactic and using recent scientific evidence calling into question the ability of individuals to discern anything reliably from facial expressions. This argument is similar to the argument regarding eyewitness testimony and line-ups.[5] Simply put, humans are not good at remembering facts and faces, we are influenced by context, and we are poor judges of truth despite what we see on “The Mentalist”.[6]

Does this evidence tip the balance? Would jurors be better judges of truth without seeing facial expressions or posture during testimony? Are these scientific findings enough to say that due process if fulfilled even if a witness wears a niqab or burka? And how does this balance with the right to confront accusers? In 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court said:

This Court’s Confrontation Clause cases fall into two broad categories: cases involving the admission of out-of-court statements and cases involving restrictions imposed by law or by the trial court on the scope of cross-examination…

The second category of cases is exemplified by Davis v. Alaska, 415 U.S. 308, 318, 94 S.Ct. 1105, 1111, 39 L.Ed.2d 347 (1974), in which, although some cross-examination of a prosecution witness was allowed, the trial court did not permit defense counsel to “expose to the jury the facts from which jurors, as the sole triers of fact and credibility, could appropriately draw inferences relating to the reliability of the witness.” As the Court stated in Davis, supra, at 315, 94 S.Ct., at 1110, “confrontation means more than being allowed to confront the witness physically.” Consequently, in Davis, as in other cases involving trial court restrictions on the scope of cross-examination, the Court has recognized that Confrontation Clause questions will arise because such restrictions may “effectively . . . emasculate the right of cross-examination itself.” Smith v. Illinois, 390 U.S. 129, 131, 88 S.Ct. 748, 750, 19 L.Ed.2d 956 (1968).[7]

Yet, this opinion does not address N.S.’s new argument. What if the fallibility or emasculation lies with the jurors? If jurors gain nothing from observing the witness or, perhaps worse make erroneous or unreliable conclusions based upon observing the witness, where does that leave the right to confront? If evidence continues to mount—creating a nearly irrefutable Brandeis brief—free exercise would likely trump the right to confront. But in the end, this same analysis would call into question the rationale for including that latter right in the Bill of Rights.

We have seen the Court reinterpret or alter the interpretation of these amendments over the course of our history, but we have not yet dealt with the increase of knowledge undermining the very rationale for an amendment. In such a situation, what should the Court do? Stick to avowed legal approaches and continue to interpret this clause fairly literally? Or can they use founders intent and suggest that the amendment does not do what the founders intended—indeed it may undermine that intent—so we move away from a strict reading of the clause? Its an interesting conundrum, especially for justices like Scalia who aver originalism.

[1] We wrote about the oral argument in this case back in 2011 (https://clcablog.wordpress.com/2011/12/15/battle-of-the-amendments-sixth-versus-first/). Here we discussed if the Supreme Court, when it faces this issues because its bound to come up in the U.S., would use the Sherbert or the Employment Division v. Smith test.

[3] http://scc.lexum.org/decisia-scc-csc/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/12779/index.do?r=AAAAAQAFbmlxYWIAAAAAAAAB

[5] See http://www.ajs.org/wc/ewid/ewid-home.asp and at this blog https://clcablog.wordpress.com/2011/09/27/due-process-and-eye-witness-testimony/

[7] Delaware v. Fensterer (474 US 15).